Catrina. If you’re familiar with Mexican culture, you’ve probably seen this iconic skull lady dressed in 20th-century European fashion without even realizing she had a name. Living in Canada, I notice that she’s famously associated with the Day of the Dead here and in the US. However, many people outside Mexico might be surprised to learn that the Catrina is not exclusively a symbol of this celebration. Instead, she originates from the values and social critiques of the Mexican Revolution in the early 20th century.

The character of the Catrina was first conceived by printmaker José Guadalupe Posada around 1910 as a satirical figure. At the time, and not so different than like today, social and economic inequality in Mexico was staggering, with more than 80% of the population living in extreme poverty. And, just as today, the elites often denied their Indigenous roots, embracing European traditions and fashion trends instead.

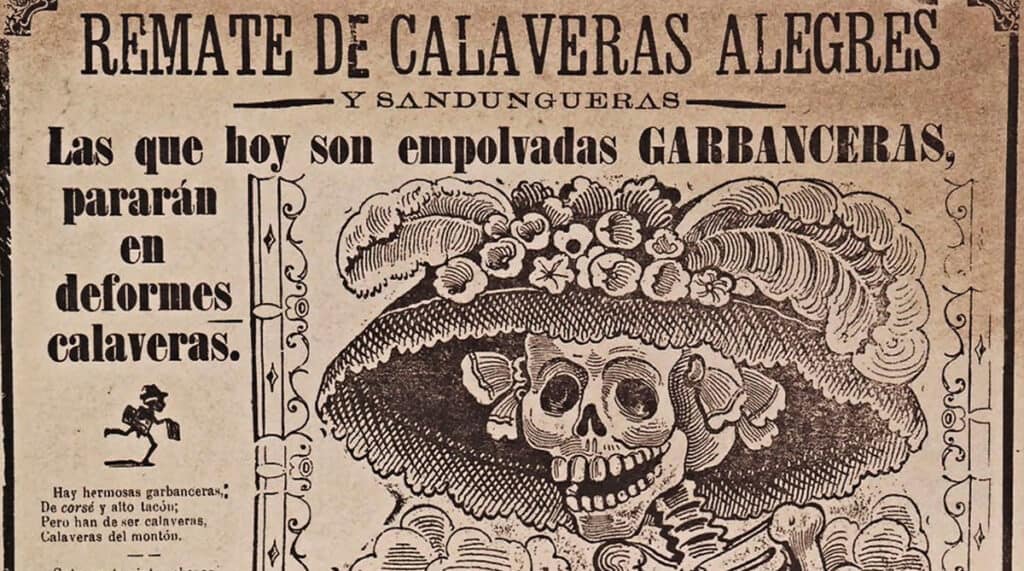

First known publication of the Calavera Garbancera in 1913.

Throughout his career, Posada created numerous skeletal figures that commented on social phenomena, political parties, and societal hypocrisies. In 1913, the image of the Catrina appeared on a political broadside with the caption:

“Remate de Calaveras Alegres y Sandungueras,

Las que hoy son empolvadas Garbanceras pararán en deformes calaveras.”

A loose English translation would be:

“The end of the merry and dancing skulls,

Those dashing Garbanceras will soon turn into deformed skulls.”

The term Garbancera referred to Indigenous women who sold foreign garbanzo beans instead of native Mexican products, symbolizing a rejection of Indigenous identity in favor of Europeanized ideals. Originally titled La Calavera Garbancera (The Garbanzo-Seller Skull), the Catrina wore nothing but an oversized, ostentatious French hat. The imagery criticized those who valued extravagant, foreign accessories over basic necessities like food or clothing.

A Catrina wearing a fruit hat. Inspired by the colorful nature you can find in the south part of Mexico.

Posada, unfortunately, died in poverty and obscurity, never achieving fame during his lifetime. However, La Calavera Garbancera and his other skeletal prints continued to circulate in political broadsides and newspapers, particularly during the Mexican Revolution. These prints were also used on the Day of the Dead to accompany calaveritas, humorous poems that honored people who had passed away. Over time, people started calling her Catrina, a name coming as a female counterpart of the Catrín, a dapper, elegantly dressed gentleman.

More than 30 years after the Catrina’s first appearance in a publication, in 1946, muralist Diego Rivera included her in the center of his famous fresco A Dream of a Sunday Afternoon in the Alameda Park, a mural depicting some of the most influential characters to Mexican culture and history. In this piece, she is depicted wearing her signature French hat, but Rivera dressed her in a traditional Indigenous outfit and adorned her with a feathered serpent scarf—a nod to Quetzalcoatl, a deity shared by several Mesoamerican Indigenous cultures.

A Dream of a Sunday Afternoon in the Alameda Park. The Catrina in the center of the image arm in arm with her creator, José Guadalupe Posada, to the right.

From that point onward, artists and crafters began reimagining the Catrina in countless ways. Today, she stands as a national symbol, embodying the complex relationship Mexicans have with their identity—balancing pride in their Indigenous roots, often stigmatized as impoverished, with the European heritage tied to a legacy of colonialism.

For me, creating my papercut Catrinas has been a way to share part of my culture here in Canada. It allows me to talk about a character that extends beyond the famous Day of the Dead and delve into the intricacies of the country I come from—a place where social classes are still sharply divided not only by income but also by cultural identity. The Catrina, however, is an icon that transcends these divisions and is understood by everyone in Mexico

A Catrina wearing Monarch Butterfly wings, a symbol of immigration from Mexico to Canada.

Under Mountains in the Moon Souvenirs

Want to display or gift one of my Catrinas?

My Catrina greeting cards make great gifts for all travel and art lovers!